As the 100m finalists of the World Championships make their way to the starting blocks at Budapest’s National Athletics Centre, a profound hush envelops the stadium that must be felt to be believed.

The emcees stop speaking, and the crowd falls silent. People take out their camera phones to capture the moment. Even those who continue to speak are shushed. This is a moment that commands and receives reverence.

The crowd agrees to a moment of silence before the race director announces “on your marks” and “get set”. The stadium erupts when the pistol fires and the race begins. Less than 10 seconds later, anticipation fills the air.

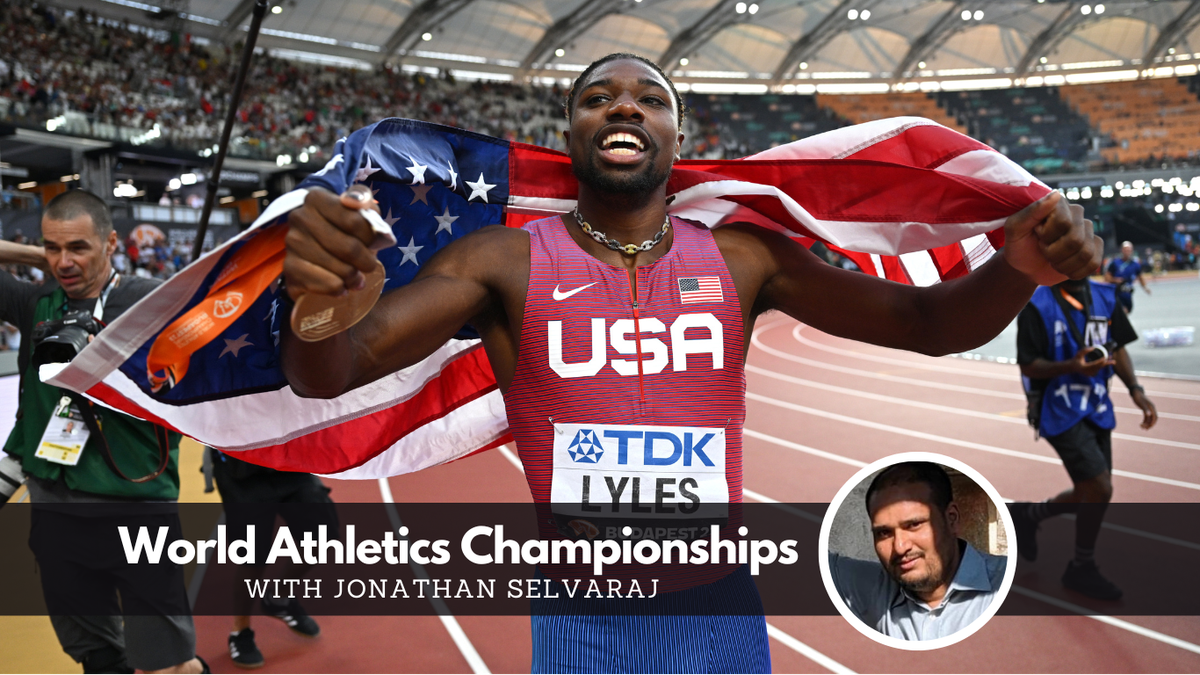

Finally, a name is listed on the scoreboard. It reads Noah Lyles, and next to it is 9.83 seconds. Lyles sees it, though he already knows the result. He finds the on-screen camera and yells, “They said it couldn’t be done. They said I wasn’t the one. But thank God I am!”. Then he wheels away in celebration, almost as if powered by the electricity coursing through the crowd.

Just a few minutes before the start of the 100m, the 36,000-strong crowd has been buzzing intermittently. Jakob Ingebrigtsen has gone from being boxed in to waving his hands in the air, demanding support, getting it, and then storming to victory in the home stretch of his 1500m race. Ivana Vuleta has confirmed her first-ever world title in the women’s long jump after Tara Davis-Woodhall couldn’t match her world-leading clearance. The hosts have won their first medal of the competition in the men’s hammer throw.

They were all great moments. But they weren’t the 100m. Before we painted in caves or beat on drums, humans ran. Nothing’s more primal to track and field than the 100m sprint. There’s no room for error, no second chances, and no pacesetters. It’s just a straight-line drag race to determine the fastest person in the world.

Track athletics needs the 100m. Ever since Usain Bolt’s retirement in 2017, the sport has lacked a star. The run-up to the Worlds saw top athletes say this out loud. Some even wondered if the sport needed a Jake Paul influencer-type character. Perhaps Lyles could be the one. He exudes charisma, knows how to make headlines, and is an anime fan. He has previously dyed his hair white and imitated Goku’s Kamehameha poses after winning races. He has mocked Olympic champion Lamont Jacobs, who has been struggling this season. On track and field forums, he has even been the subject of hate posts. In pro wrestling terms, he is a heel with heat. He recently posted on Instagram that he could break Bolt’s record in both the 100m and 200m events, taking aim at some of athletics’ most respected figures.

It was an assessment that defending World Champion Fred Kerley scoffed at, saying if Lyles did that, he’d run faster. “I’m Fred Kerley, and it’s my title,” Kerley said. “If Noah runs 9.65, I’m running faster.” Lyles responded, “That’s what they all say until they get beat.”

Kerley, though, didn’t make it out of the semifinal round.

For all of Lyles’s bluster, the fact is that he’s proven he can back it up when it matters. Despite starting slow in the 100m race, Lyles overtook his opponents from Lane 6 and won the race. He is a 200m specialist and is expected to defend his world title later this week. That’s something a certain Jamaican used to do quite well.

It’s not taken Lyles too long to appoint himself the heir apparent. At the press conference following the race, Lyle’s personality was starkly in contrast to Letsile Tebogo, a 20-year-old from Botswana, who finished in 9.873 and became the first African to place on the podium at the Worlds, and Britain’s Zharnel Hughes, who took bronze in 9.874.

Tebogo dedicated his win to South Africa’s Akani Simbine, who had been carrying Africa’s hopes, reaching the final of the last four world events. Hughes tearfully thanked his mother for backing him when he lacked self-belief early in his career. Lyle, meanwhile, talked about winning the 200m race and the 4x100m relay. “It’s time to start a dynasty,” he beamed.

It’s probably too early to suggest anything like that might happen. Lyles is admittedly quite quick, and he might well believe he’s got a shot at cracking Bolt’s 19.19 mark in the 200m, a race the American knows like the back of his hand. He’s run very fast for 200 meters this year — his 19.47 in Monaco was the 10th-fastest performance ever and the fastest anyone—Bolt included—has run before a major championship — none of his 100m races suggests the potential for a 9.65. His personal best stands at 9.83, and it’s virtually unprecedented for someone at Lyles’s level to chop off more than two-tenths of a second as quickly as Lyles says he plans on.

More than a few will have things to say about his plans for a dynasty. Oblique Seville narrowly missed out on winning Jamaica’s first bronze medal in the men’s 100m at the World Championships since Usain Bolt won the same medal in 2017. Ryiem Forde also made the final, marking another first for Jamaica since 2017. Both Forde and Seville are 22, while Tebogo is 20 and Lyles is 26.

Lyles might have won bragging rights for this year with his win at the Budapest Worlds, but you know that everyone gets to run this one again. The athletes will be ready, and for sure, so will the fans.