HAMBURG, Germany, Apr 07 (IPS) – Geologists have described the region as the most similar to Mars on Earth. Whether it’s violent sandstorms or ice found on its surface, we get more news from the red planet than from Balochistan.

“I still don’t understand how a territory divided by the borders of Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan remains so unknown to the rest of the world. I can’t think of a people who receive as little attention as the Baloch,” Martin Axmann told IPS.

This doctor in Political Science and author of one of the most referential recent books on the Baloch question – Back to the Future (Oxford, 2008) – points to a strategic territory the size of France which boasts huge reserves of gold, gas and uranium.

Axmann is one of the speakers at a conference organized by the Movement for a Free Balochistan – a political organization with a “secular and democratic” project -, on the 75th anniversary of Balochistan´s forced annexation by Pakistan.

Today it is the most depopulated province, the one with the highest rates of illiteracy and infant mortality, and the one most affected by violence. It´s also the most hermetic one.

The German expert would not have been able to access the area if he had travelled as a journalist. The few that have tried have been expelled from the country and banned, or even worse.

Carlotta Gal was a correspondent for The New York Times when she was brutally beaten in Quetta – the provincial capital, 900 kilometers southeast of Islamabad – in 2006 by a group of men who identified themselves as “members of a special section of the Pakistani police.”

They told her that she lacked permission to be in Quetta.

After nine years as an Islamabad correspondent for The Guardian and The New York Times, Declan Walsh was expelled from the country in 2013 for “undesirable activities”. He had written an article about the missing Baloch in Pakistan.

Due to this firewall against the foreign press, the responsibility for reporting falls exclusively on local journalists. Pakistani journalist and best-selling author elaborates on this:

“Reporters on the ground face constant threats from Pakistani secret services, Baloch movements and sectarian groups. We often never get to find out who is behind many of the attacks,” Rashid told IPS by phone from his residence in the Pakistani city of Lahore.

He claims that many of his colleagues resort to “self-censorship”:

“It’s simply not reported. And if Balochistan is not in Pakistan’s media eye, it will not reach the outside world either as most of the Western media is fed by press agencies.”

In its latest report on press freedom worldwide, Reporters Without Borders ranks Pakistan 157th, describing it as “one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists.”

The Balochistan Union of Journalists points to more than 40 journalists killed in Balochistan between bomb blasts and targeted killings, some of them committed outside the country.

Sajid Hussain’s body was found Baloch in a river on the outskirts of Uppsala (Sweden). RSF then pointed to the possibility that it was the work of Pakistani agencies.

“Eight months later, the body of Karima Baloch, a Baloch activist and human rights defender, was rescued from the waters of Lake Ontario (Canada). The BBC had included her on its list of “the 100 most inspiring and influential women” of 2016.

On “ground zero”

“When you are a journalist in Balochista, it is the security agencies that contact you directly: they call you by phone, they reach out when you cover a press conference, a protest in the street…”.

Thus begins the story of Ahmad, an exiled Baloch journalist who prefers not to disclose his full name or country of residence to IPS to avoid reprisals on his family back home.

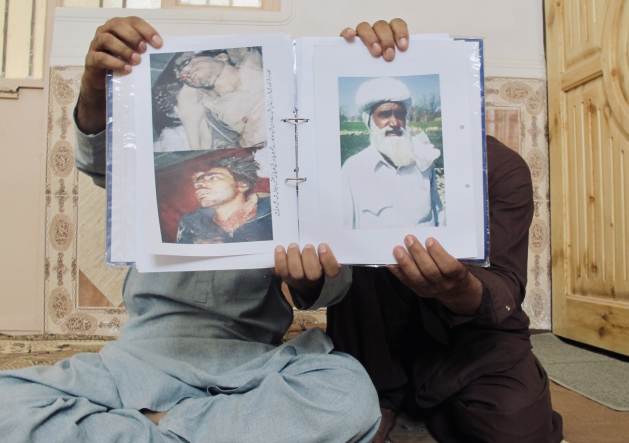

“One of the most sensitive stories is that of the enforced disappearances. In the eyes of the agencies, the simple fact of speaking with their relatives means that you are working against the State,” underlines the Baluch man on a videoconference.

In 2022 alone, Amnesty International reported more than 2,000 cases in Pakistan, a phenomenon that the NGO describes as “frequent” in the province of Balochistan .

Ahmad recalls how difficult it was to cover the news about Balochistan, and also that phone call while he was covering the story of a murdered colleague:

“We know who you and your brothers are. We also know that you have two children, what school do they go to… Do you want them to stay alive?” he was told over the phone.

Ahmad soon realized that he was being followed. A few days later, he was run over while riding his motorcycle to work.

“I was lucky to get out unharmed and that there were a lot of people around. The car turned around and left,” recalls this journalist who left the country soon after.

It was the same threats that pushed Kiyya Baloch into exile. He´s a seasoned reporter with several publications The Guardian , The Telegraph or the BBC .

“That pressure ended up affecting my family. They couldn’t stop thinking that I could be assassinated at any moment,” told IPS over the phone this reporter who prefers not to reveal his current coordinates.

“I even receive threats in this country where I am now,” he apologizes, before pointing to other coercive measures.

“The Government also puts the pressure on the media so that they do not hire you, or you get fired; they drown you financially in order to cut your wings as a journalist until. Eventually, you end up leaving the country,” adds Baloch.

Listening to the BBC and Voice of America radio broadcast at home from a very young age was what sparked Zeynap’s vocation . She chooses a random name in order to protect herself.

She speaks from “ground zero” and from a “much more fragile” position than that of her male colleagues.

“We share with them the fear of state surveillance, but then there are those cultural barriers that only us, women, face,” the reporter told IPS by phone.

An example of that, she explains, is how women are perceived in those “all-men protests.”

“You want to do your job but at the same time, want to respect the culture so at the end, you heavily rely on sources. Even if you are not very far from the place you are researching, you make phone calls to ask others instead of going to the spot yourself”, she explains.

Zeynap points to “human” issues beyond the purely political. “Did you know that more than half of the girls here do not go to school? Few issues seem more important to me than this one,” she stresses.

How to tell that and other stories from Balochistan to the outside world?

The reporter recalls the veto on international NGOs, and she also does not foresee any changes in the government’s policies towards journalists.

“The international community and human rights organizations will have to step in,” says Zeynap. “I do not see any other way around.”

© Inter Press Service (2023) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service